October Case of the Month

Scooter (left) enjoying the beach!!

For October’s Case of the Month, I have selected a relatively common problem that we see in veterinary medicine – cranial cruciate ligament ruptures. Cranial cruciate ligament (CrCL) ruptures (more commonly referred to as an ACL tear after the human literature) are commonly seen in the practice of veterinary surgery, in fact they are our most common orthopedic case that we see. This disorder affects both the large and small dog, from the Great Dane to the Chihuahua and can affect dogs of any age most commonly the middle age dog. If you would like further details about this specific disorder, please see the previous posts regarding cranial cruciate ligament ruptures (click on the orthopedics tab in the menu bar).

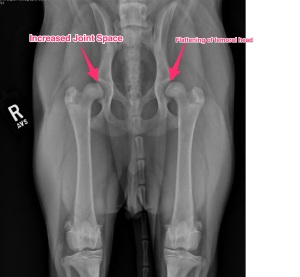

Scooter is a 5 yr old Labrador Retriever that presented for lameness in both hind limbs. His history was such that he was lame in the left hind limb about a year ago and had a previous surgical procedure to address the CrCL performed, to which he responded well early on but became increasingly lame again in the leg and then developed a right hind limb lameness in addition. The procedure previously performed on the left stifle (knee) was not documented and no radiographic implants were used in or around the stifle. Also, Scooter has a chronic history of hip dysplasia and osteoarthritis in both hips to compound his issues.

Physical Exam:

Scooter could walk with assistance, however really struggled in both hind limbs to ambulate. Also, you could see Scooter shifting his weight to his front legs, which is a very classic feature for dogs with CrCL ruptures that affects both stifles. Our physical exam revealed that both (left and right) CrCL were ruptured and we highly suspected bilateral meniscal injuries/tears. While some discomfort could be elicited from manipulation of his hips, the majority of his discomfort and inability to walk was from his CrCL ruptures and meniscal tears.

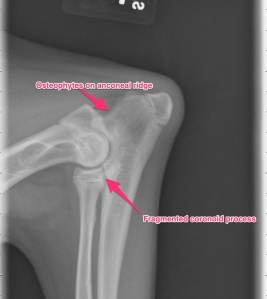

Right knee – note the joint swelling, arthritic changes, and forward movement of the tibia in relation to the femur.

Left knee – note the joint swelling, arthritic changes, and forward movement of the tibia in relation to the femur.

VD pelvis x-ray – note the chronic signs associated with hip dysplasia.

Surgery:

Surgery was scheduled soon after his initial exam, all his pre-operative work-up was otherwise normal. Most of the time we try to stage each leg. The big reason for separating out surgery on each leg is to reduce the risk of complications such as infection and implant breakdown. Some cases, like Scooter, we chose to do both especially if they are severely affected on both legs like Scooter.

At surgery, bilateral cranial cruciate ligament ruptures were noted, along with bilateral medial meniscal tears. All those findings can be very painful for the patient. Both meniscal tears were debrided (removed) and bilateral tibial plateau leveling osteotomies (TPLOs) were performed. For more detailed information about ways we correct CrCL tears, please view that page on this website.

Right knee – following TPLO surgery.

Left knee – Following TPLO surgery.

Post-operative care:

As you can image, we treat these patients very carefully. In human medicine, physical therapy and rehabilitation is started almost immediately following surgery. As soon as a patient leaves the operating room, we start icing of the surgical site. That is followed but passive range of motion exercises and short, assisted walks and frequent icing after sessions during the first two weeks. A fairly strict physical therapy program is given to owners and in some cases, organized physical therapy sessions are scheduled under the supervision of a certified canine rehabilitation therapist (CCRT). I generally tell the owners that their commitment to physical therapy is as important as the surgery performed. In Scooter’s case, his owners were very dedicated to the whole process and 16 weeks later he is back to doing his normal activity, which includes running, swimming, and of course lounging around from time to time.

Swimming at dusk.

Happy dog basking in the sun!!

Scooter and his buddy enjoying a swim!!