Sometimes it can be very hard to determine which leg your pet (or patient) is limping on, let alone which joint is causing the problem. I want to take a little time to discuss a problem that we see from time to time that typically affects the juvenile (6-18 month), medium and large breed dog and is typically thought of as a congenital/hereditary issue. The most note worthy joints affected are the shoulder (proximal humerus), the elbow (distal humerus), stifle (distal femur), and hock (talus).

The underlying etiology is similar in all the joints, however this article will focus on the shoulder with subsequent articles dealing with the other joints. I think this approach is reasonable because the treatment may be different for other joints,as well as, the prognosis can vary. Again, this disease affects primarily young dogs; in the older patients we usually see the consequence of this issue, resulting in osteoarthritis of the joint.

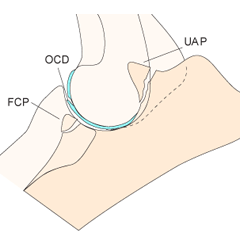

Osteochondrosis (OC) precedes osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) and is characterized by a problem between the metaphyseal growth plates of the affected bone and the cartilage. In essence, the cartilage surface does not adhere to the underlying subchondral bone surface. When a cleft or break develops in this “soft” cartilage, this fulfills the term OCD. Once the area progresses to an OCD lesion (a break in the cartilage develops), then the patient becomes clinically lame and will exhibit a degree of lameness/limping. Once a flap/break develops there is no known healing that occurs and the abnormal area will continue to incite inflammation within the joint.

There are multiple suspected causes of this issue in the dog, with the most reasonable explanation being that of a congenital/hereditary cause. There is some support of other predisposing factors that may enhance the genetic expression of this disease such as juvenile obesity and imbalances in calcium intake.

Patients with this type of condition will usually be within 6-18 months of age and have a varying level of lameness on one or both front legs. An owner may also see more limping/lameness after strenuous activity or rising from rest.

Physical examination of the suspected patient usually will direct us in the right direction. A thorough gait evaluation is needed to identify which leg or if both front legs are affected. There are certain techniques that can be used to detect which leg is the culprit even with a mild lameness. If your dog is “off and on” lame, it is always helpful to the veterinarian for the owner to bring in video of the patient when he is limping, to help improve our chances of diagnosing your pet correctly. The next step in the evaluation is direct palpation of the leg starting from the digits, working up to the neck. It is very important that care is taken at each joint and long bone on evaluation, since shoulder OCD is not the only cause for limping in the young dog. Typically, discomfort will be elicited on manipulation of the affected shoulder(s) and especially on hyperflexion and hyperextension of the joint. The next step is diagnostic tests.

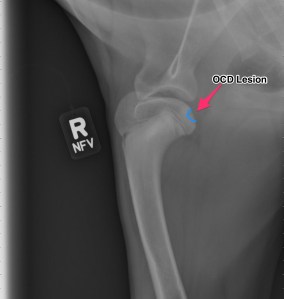

Radiographs (X-rays)

Above are x-rays of a left and right shoulder affected with OCD lesions. These are on the same patient. The images labeled with the left (L) marker has a flattened region noted by the arrow which is characteristic of OCD. The image on the right has the area highlighted in blue. While the lesion doesn’t look big, it can definitely cause a lot of pain and discomfort.

Another way to diagnostically evaluate the joint is with a computed tomography (CT) scan. This will give more detail into the region of interest. Generally this is not needed, however indications for it may be to evaluate the elbows as well.

Treatment:

For the best possible outcome do not delay treatment! At this time, the gold standard approach is arthroscopic debridement (removal) of the fragmented cartilage and the surrounding diseased cartilage and subchondral bone. Curettage may allow the now vacant cartilage bed to fill in more quickly with what is called fibrocartilage. I likened the removal of the fragment to old wallpaper removal (very much oversimplified). Once the old wallpaper bubbles and tears, you need to remove all the damaged wallpaper in the periphery or else the wallpaper will continue to peel.

If the cartilage is an osteochondrosis (OC) lesion and has not fragmented (OCD) non-surgical treatments (activity restriction, dietary restriction, etc) may be attempted and successful. Unfortunately, if OCD has not occurred then the patient will not be limping and most of these dogs go undiagnosed. It is my belief that any dog exhibiting pain/lameness with the presence of a radiographic (x-ray) OCD lesion ,should have surgery. Surgery will benefit them both in the short term and the long term.

There are older techniques of opening the joint to get access to the cartilage flap, however the recovery time on this type of procedure is significantly longer than with arthroscopy. Also, potential complications are increased with an “open” technique than with arthroscopic techniques. Arthroscopy is a minimally invasive tool that allows us to both diagnose and treat this condition. Generally speaking the patient can walk on the surgery leg (even if both legs have surgery at the same time!) following an arthroscopic procedure. Generally 2-3 small ports are placed over the shoulder (2-4mm in length) and this allows us access to the joint and work within the joint.

Recovery and Rehabilitation:

Recovery for the arthroscopic procedure is generally 4-6 weeks. Every surgeon has a different protocol for after surgery and I am very respectful of that. I prefer controlled movement for my patients. In the first two weeks, passive range of motion is very important, followed by active icing of the joint(s). Short leash based walks are started shortly after surgery and incrementally increased as we proceed through the recovery phase. Introduction into a formal rehabilitation program is recommended, however there are times when this is not possible and rehabilitation must be performed at home. Below is a patient that had a single shoulder arthroscopy, you can see how well they can walk following surgery (this is the following day)!

Prognosis:

When diagnosed and treated early, the dog affected with OCD can have a good prognosis and resume a normal or near normal activity level and quality of life. The longer the lesion is present, the more inflammation and arthritis will develop decreasing our success with surgery. Of the OCD lesions (shoulder, versus the other sites affected) this region has the best prognosis. I do encourage all my patients to continue on joint supplementation for life and to be removed from any breeding program.