Spring and summer bring about so many good things: the beach, warm weather, family gatherings, to name a few; and then some bad things: bugs, sweltering heat and humidity, allergies, and the list goes on. For your pets, especially your older retrievers and short nosed (brachycephalic) breeds like the pug and bulldog, the heat and humidity can spell danger due to airway conditions. For more information on the brachycephalic dog breathing issues, see my other post http://wp.me/p2vvxS-2R . This article will focus on a condition called laryngeal paralysis which typically affects our large breed dogs, such as the Labrador Retriever and similar breeds, although it has been seen in cats (rarely) and is a defined disease process in horses.

What is laryngeal paralysis?

Laryngeal paralysis can be as bad as it sounds. The larynx is at the back of the mouth and allows the passage of air into the windpipe (trachea). In the video below, it mimics swinging doors and the cartilages (arytenoid cartilage) that form the larynx will open when breathing “in” (inspiration) and open when breathing “out” (expiration). It remains closed during other actions, like eating and swallowing, thus stopping food, water, saliva from going down the trachea. There is a muscle that controls the opening of these cartilages. The muscle (cricoarytenoideus dorsalis muscle) sits on top of the cartilages on both sides and actively contracts to open the cartilages during inspiration. The opening of the cartilages when exhaling is passive as the air blows open the cartilages. Laryngeal paralysis is a condition where the nerves that feed this muscle are not working properly and the muscle atrophies and is nonfunctional – hence the larynx is paralyzed and can’t move normally.

What causes this condition???

In most dogs, we do not know the reason for this condition. We divide the condition into two general types: 1. congenital and 2. acquired. In congenital, this condition is usually seen at an early age and is thought to be hereditary. Some common breeds affected are Siberian Huskies, Bulldogs, Rottweilers, etc. In the second form (acquired), it simply means that the disease occurs secondary from other issues. When we think of causes we have to ask ourselves, what can cause damage/changes to the nerve (recurrent laryngeal nerve) that feeds the cricoarytenoideus dorsalis muscle? Conditions that we evaluate for typically are as follows: cervical (neck) tumors, chest/lung tumors, myasthenia gravis, peripheral neuropathies, previous neck (cervical) trauma, and endocrine diseases. Most of the time, we do not find a direct cause and suspect an undiagnosed peripheral neuropathy as the underlying cause. When we do not know the actual cause we term the disease “idiopathic”. Some recent studies (Stanley, et al) have shown that most (if not all) patients with idiopathic laryngeal paralysis will begin to display some generalized neurologic signs within 1-2 years following the diagnosis.

What are the signs of acquired laryngeal paralysis???

Typically, this affects our larger breed dogs, with the Labrador Retriever being the poster child for this disease. The dogs affected are generally middle to older in age, and either male or female. The most common signs noticed is difficulty breathing, especially when exercising or excited and gagging/coughing when eating/drinking. This is a progressive disease, so signs usually begin with mild changes and become more severe, which can be over months to years. You may also notice a change in the pitch of your dogs bark (voice). Most of the time, we can arrive at a presumptive diagnosis just listening to your pet breathing. As the disease progresses, the affected dog becomes more at risk, and can have a respiratory emergency if not managed appropriately, which can be fatal. Below is a video (the audio is most important) of a dog with laryngeal paralysis:

What diagnostics are involved with laryngeal paralysis???

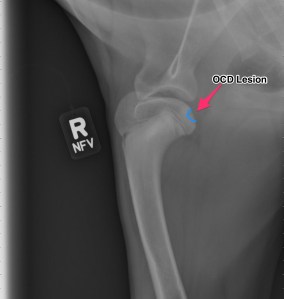

To begin, a thorough general and neurologic examination is needed for your pet. At minimum, a complete blood work, including a thyroid screening panel, and chest (thoracic) x-rays are needed. The importance of these is to look for other disease processes that may be going on and to ensure that the major organs are functioning appropriately. Why the thyroid panel? Hyopthyroidism (low thyroid hormone production) can cause various neuromuscular issues. With the chest x-rays we are looking for any masses, changes to the esophagus size (megaesophagus) and signs of aspiration pneumonia, which can be seen secondary with laryngeal paralysis. Because most of the patients I see with this condition are older and we are assessing for surgery, I highly recommend an abdominal ultrasound by an experienced ultrasonographer to look for any other concurrent diseases. Bear in mind, if your pet is in a respiratory crisis some of these steps may be done out of order to adequately stabilize the patient.

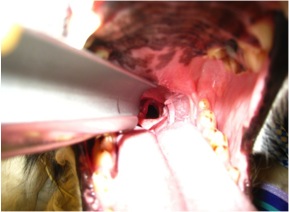

The best way to confirm the suspected diagnosis of laryngeal paralysis is to look directly at the larynx and assess the functioning of the laryngeal cartilages. This is typically done by inducing a light plane of anesthesia and looking at the back of the mouth. The proper assessment is sort of an art and takes practice to be comfortable making the diagnosis. In addtion to evaluating the larynx, time is taken to look at the rest of the oral cavity for other potential causes. As a surgeon, my preference is to do this examination directly prior to surgery to minimize the amount times the pet needs to undergo anesthesia.

Below is a video demonstrating laryngeal paralysis. The laryngeal opening can be seen and you will notice that it is not moving much at all during the phases of breathing.

How can I treat my pet once laryngeal paralysis is diagnosed???

Probably the better questions is when do I treat? Once a diagnosis is made, then a decision needs to be made. Since this is a progressive disease, if only one side of the larynx is affected then surgical options will most likely be delayed. The most typical treatment for idiopathic laryngeal paralysis is surgical. To date, there is no medical therapy that will restore the function of the larynx. Conservative management will typically incorporate ways to keep your pet cool (air conditioned environment), sedation possibly, and decreasing environmental allergens. If, during our pre surgical diagnostics, we find other issues, changes may be made to the treatment plan. There are some findings that may make your veterinarian reconsider your pet being a good surgical candidate, such as an enlarged esophagus (megaesophagus). The main reason to proceed forward with surgery is to improve your pets quality of life for however long that may be, as well as improve your (as the owner) life by providing more quality time together. There are risks both with surgery and without surgery.

The standard procedure to open the airway is called an arytenoid lateralization (laryngeal tie-back). This is a procedure that pulls one side of the laryngeal cartilages back, permanently opening one side of the larynx. In effect, we override the normal muscular action of the larynx. We gain access to the larynx by an incision made on the side of the neck. None of the work is done within the mouth. There are other procedures that remove the arytenoid cartilage portion of the larynx to permanently open the larynx from within the mouth, called an arytenoidectomy. This procedure, in my opinion, has not been evaluated as much as the “tie-back” procedure.

Below is a picture of an arytenoid lateralization. Notice the difference on the opening from the previous video.

What are the risks with and without surgery and what is the typical outcome?

No procedure is without inherent risks, unfortunately. The risks and benefits of any procedure must always be weighed and discussed with your veterinarian and veterinary surgeon. The most common post-operative complication is aspiration pneumonia. Recent literature cites about a 12-15% risk of aspiration pneumonia following surgery, with the most critical time period being the actual recovery from surgery and the immediate post-operative period. Some medications can be administered that help reduce vomiting, regurgitation and increasing the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter muscle – all aimed at lowering this risk. Most of the time aspiration pneumonia, if caught early, can be treated successfully with antibiotic therapy and supportive care (depending on severity). In a small number of patients, aspiration pneumonia can be fatal. Other complications are break down of the “tie-back” suture and incisional complications such as seroma and abscess/infection. Anesthesia complications can arise with any anesthesia/surgical event, however with proper screening, this risk can be minimized. My feeling is that even dogs prior to a “tie-back” procedure have a higher risk of aspiration pneumonia because the protective mechanism of the larynx is not functioning properly.

Surgically addressing this condition can be life saving and drastically improve the quality of your pets life. Most owners (~90%) are happy they made the decision to proceed forward with surgery and are pleased with the improved quality of life for their pet. If you notice any of these changes to your pet, please plan to see your veterinarian to see if they are a candidate for surgery. While the above article is long, it does not include everything related to this disease, if you have questions, just ask!!!

Kevin Benjamino, DVM, DACVS

Copyright 2015